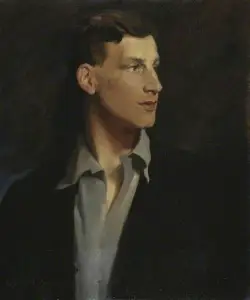

This study of the life of the poet Siegfried Sassoon is written and directed by the English auteur Terence Davies. I don’t normally use that somewhat pretentious term to describe a moviemaker, but am making an exception in Davies’ case because his elevated standing in the world of cinema does warrant it.

Davies takes his work so seriously that he only makes a feature film on average once every four years. These are invariably lauded by critics. In fact he’s won more awards than he’s made movies, by the looks. These carefully nurtured works often end up labelled classics.

His first feature-length film, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) was the first in a trilogy which explored his early life as a young gay man growing up in a repressive working class Catholic family in Liverpool.

When not examining his own troubled past, he tends to take inspiration from serious literature: The House of Mirth (2000) is an adaptation of an Edith Wharton novel, The Deep Blue Sea (2011) is an adaptation of a Terence Rattigan play, and his last film, A Quiet Passion (2016) is about the life of American poet Emily Dickinson.

Siegfried Sassoon is one of 16 Great War poets commemorated in Westminster Abbey. I hadn’t known there were that many. I knew of Rupert Brooke and Wilfred Owen, both of whom were killed early in World War I. It was Rupert Brooke who wrote that exquisite sonnet The Soldier, that begins:

If I should die think only this of me/that there’s some corner of a foreign field that is forever England.

I used to tear up over that one as a lass, in the days when we were allowed to be proud and sentimental about our English heritage.

But I digress. That was Rupert Brooke, and he doesn’t feature in this story. Wilfred Owen does. He and Sassoon met and became lovers when both were inmates at a military psychiatric hospital during the war. Sassoon had been sent there as a soft punishment (he being of the right class) for having publicly criticized the conduct of the war – the jingoism, the senseless mass slaughter – although he himself had served with almost foolhardy bravery in combat.

Owen and Sassoon worked together on Owen’s draft of the famous anti-war lament Anthem For Doomed Youth, which also tears me up, and the first lines of which go:

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle? — Only the monstrous anger of the guns….

Owen was sent back to the front and was killed a few days before the war ended, In November 1918. Sassoon survived and went on to take his place among the fabled figures of the literary and artistic avant-garde of the time.

In an early scene we see him and other aristocratic Bright Young Things attending the 1921 London premiere of Stravinsky’s revolutionary Rite of Spring. In due course we meet Lady Ottoline Morrell (of Bloomsbury fame), the poet Edith Sitwell, TE Lawrence (of Arabia), Ivor Novello and Stephen Tennant. Much of the film’s narrative is taken up with Sassoon’s turbulent and dangerous love affairs with the emotionally ruthless Novello – the Elton John of his day – and the decadent socialite and aesthete Tennant.

Memories of Oscar Wilde’s fate are fresh. Lord Alfred Douglas – Wilde’s beloved Bosey – is gossiped about scurrilously and warily. These gay blades may be on first name terms with Winston Churchill and TS Eliot, but despite their elevated social standing, they may not yet speak freely the name of their forbidden love.

Siegfried Sassoon lived till 1967, and even married and had a son. Over the years he became alienated from the smart set, rejecting their meaningless hedonism and nursing growing guilt and disgust about what he came to see as the degeneracy of all their lives. Later in life, as a widower, he converted to Catholicism, a fact which has obvious echoes in Davies’ own life.

Davies sketches in these later years, but never loses sight of the defining event which overshadowed Siegfried Sassoon’s life: the Great War and its attendant horrors.

He constantly reminds us of this by interspersing his narrative with long sequences of WWI battlefield footage. For us moderns those old images – gaunt tin-hatted men moving jerkily through a grey landscape of exploding mud and lifeless corpses – has become a kind of ho-hum shorthand for an unthinkably miserable and best forgotten old conflict whose participants are now all dead. In less assured hands it might have become tedious, but here, overlaid with recitations of Sassoon’s lucid heartfelt verse, it gives the film its moral and emotional heart.

The scripting is intelligent, the acting excellent, the historical setting is flawlessly recreated. The music too is used to marvellously evocative effect – another Davies trademark.

I’ve been wondering about the film’s title. A benediction is a blessing, taken from Catholic ritual. Perhaps Davies intends us to see Sassoon’s poetry as a kind of redeeming feature – a final blessing – to be salvaged from the folly and suffering of the Great War.

Taking your peaceful share of Time, with joy to spare. /But the past is just the same – and War’s a bloody game …Have you forgotten yet? …Look down, and swear by the slain of the War that you’ll never forget.

Siegfried Sassoon, Aftermath