I’d never heard of Lee Miller until I caught the buzz around this movie. Sounded good. Then I listened to an interview the ABC did with her son Antony Penrose. In it he painted a picture of a truly remarkable woman who’d led an astonishingly adventurous and creative life.

In short, Lee Miller was a one-time Vogue model who became an intrepid frontline photographer embedded with the Allied forces during World War II. She once famously had herself photographed in Hitler’s bathtub. Later in life she and her husband Roland Penrose became leading lights of the postwar artistic world in France and the UK and hung out with the likes of Picasso, Dora Maar (Picasso’s wife and model/muse), Max Ernst (German expressionist) Paul Eluard (famous French poet), Man Ray (cool surrealist photographer), and Cecil Beaton, (English society portraitist).

In the interview Antony Penrose tells how his mother became a model. In 1927, aged 19, slim, beautiful and stylish, she steps off a Manhattan street into the path of an oncoming vehicle. A man whisks her to safety just in time and she faints in his arm. He turns out to be the publisher Conde Nast, and he decides there and then she must model for him. Within a few months her face is on the cover of Vogue. She becomes a fixture on the New York social scene and hobnobs with the likes of Charlie Chaplin, George Gershwin and the Vanderbilts.

I can’t resist reproducing this extract from a recent article in Tatler magazine:

Fashion greats such as photographer Edward Steichen zipped her into Lanvin and Lelong, draped her in pearls, swathed her in velvet. In one picture she models a Chanel evening gown covered with geometric embellishments, her body resembling a glorious art-deco building. She was fêted and pursued by suitors. A glassware manufacturer even moulded a champagne coupe in the shape of her breast.

Vogue sends her to Paris where she meets Man Ray in a bar, decides she wants to be on the other side of the camera and that he’s going to teach her photography. He says he doesn’t take students and is off soon to Biarritz. She says ‘I’m coming with you’, and that was that. She becomes his mistress and an accomplished photographer.

When the war broke out she persuaded Vogue to make her their war correspondent. She was brave to the point of recklessness while embedded with the American army, and perhaps more significantly at war’s end when she and Life photographer David Scherman unflinchingly recorded the horrors of the death camps.

It was Scherman who photographed her taking a bath in Hitler’s Munich apartment on the day of his suicide in the Berlin bunker.

Long before Penrose had got to this bit in the interview I had naturally decided to take myself off to see Lee at the first opportunity.

And I have to say I was a bit disappointed in it, and not just because it almost exclusively tells the war story and leaves out the fun stuff.

Director Ellen Kuras is an award-winning cinematographer, and it shows in her recreation of the chaos, ugliness and devastation of war and its aftermath. There are some powerful scenes: badly wounded American soldiers lie dying in camp hospitals, French women are seized by vengeful citizens and publicly shamed for going with Germans, starving dead-eyed concentration camp inmates wander aimlessly, a pile of corpses spills out of a cattle-truck abandoned by the fleeing Germans.

The trouble is it’s almost more a documentary than a biopic, as if it was made to showcase Kuras’s cinematographic skills rather than to create a portrait of a remarkable woman. Obviously it would be impossible to tell the full story of such a splendidly multifarious life in one feature film, but we come out of the movie with not much understanding of Lee Miller as a person.

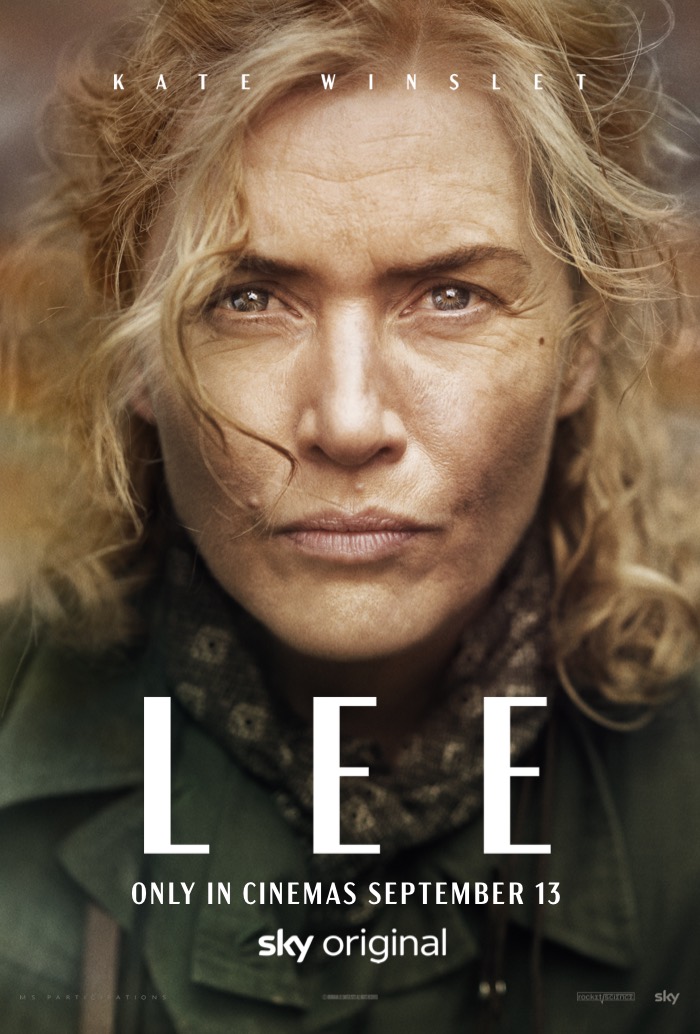

Kate Winslet is very good in the lead role, but there are inconsistencies of character development. Right from the start she’s portrayed as stoic, hard-bitten and emotionally impervious, even through the worst of the suffering, death and destruction, until in one incongruous scene she suddenly goes to water and starts hyperventilating like a millennial snowflake while flipping through her own photos. It doesn’t ring true.

I think the problem is with the script. Here’s another instance. We had been briefly introduced to her pre-war circle of bohemian friends, but only very cursorily; they are no more than visual human wallpaper to set the scene for Miller’s first meeting with her future husband. A bit later, as war approaches, he mentions that some of them have had to go into hiding. It’s not clear whether this is because they are Jews or partisans. After the war they come back into the story, kind of, as a handful of nondescript survivors we barely remember. There’s one overlong scene in which Miller finds one of the women, by now a nervous wreck, pathetically trying to sweep up some mess in her still elegant Paris apartment. Miller hugs and cossets her, but the melodrama falls flat because we essentially don’t know who this woman is. I had a cynical suspicion that the cinematographer/director was more interested in the visuals of the apartment, which still looks habitable despite the mess on the floor.

There’s another scene showing Miller feistily warding off a GI about to force himself on a young French girl. I knew from the interview that she had suffered a sexual assault by a family friend as a child, but we only learn about this in the film when she is shot in intense close-up trying to describe this event to someone and saying ‘it happens all the time and they’re still getting away with it.’ This sits uneasily with the more immediate, vastly more harrowing horrors of death camps and corpse-filled cattle-trucks she had just witnessed and recorded. This was not the time, I thought, for a gratuitous #MeToo moment.

The narrative unfolds as a series of flashbacks framed within an interview by a younger man (Josh O’Connor – Prince Charles in The Crown) quizzing an older Miller about her life. At the end he’s revealed to be her son Antony, but I couldn’t see the point in the storytelling being so coy about his identity. It was easy to guess and nothing hung on it dramatically.

It was Antony who retrieved from obscurity the archive of his mother’s wartime photographs, which had lain hidden in an attic until his wife found them after Miller’s death in 1977. The publication of that archive led to a reappraisal of her importance as one of the most significant photographers of the 20th century.

Lee draws on a biography Antony Penrose wrote about his mother in 1985: The Lives of Lee Miller. (He wrote a lot about both his parents. His father Roland Penrose has his own Wikipedia entry, as does Antony. Have a look: their lives are as worthy of cinematic biographies as Lee’s is.)

This movie does us a service in bringing this brave woman’s story to the attention of a new generation. Due justice is done to the awful gravity of the events that prompted her most important work, but it’s a pity that so much time is wasted on awkward melodrama which at times swamps her personal story.