Everyone knows Hallelujah, Leonard Cohen’s modern hymn to spirituality. Not many people know all the words (I know a few verses – I’m annoying that way) but everyone knows that stately ascending melody – the fourth, the fifth – and everyone knows to chime in with hallelujah! when it comes after the minor fall and the major lift, and everyone can do those sweet lilting repetitions in the last line.

Those bits are easy to harmonise with, and I speak as someone prone to bursting into song in the shower or with a few sherbets under my belt. Judging by the number of players who know it among those who turn up at parties with guitars, I gather the chords are easy to play too.

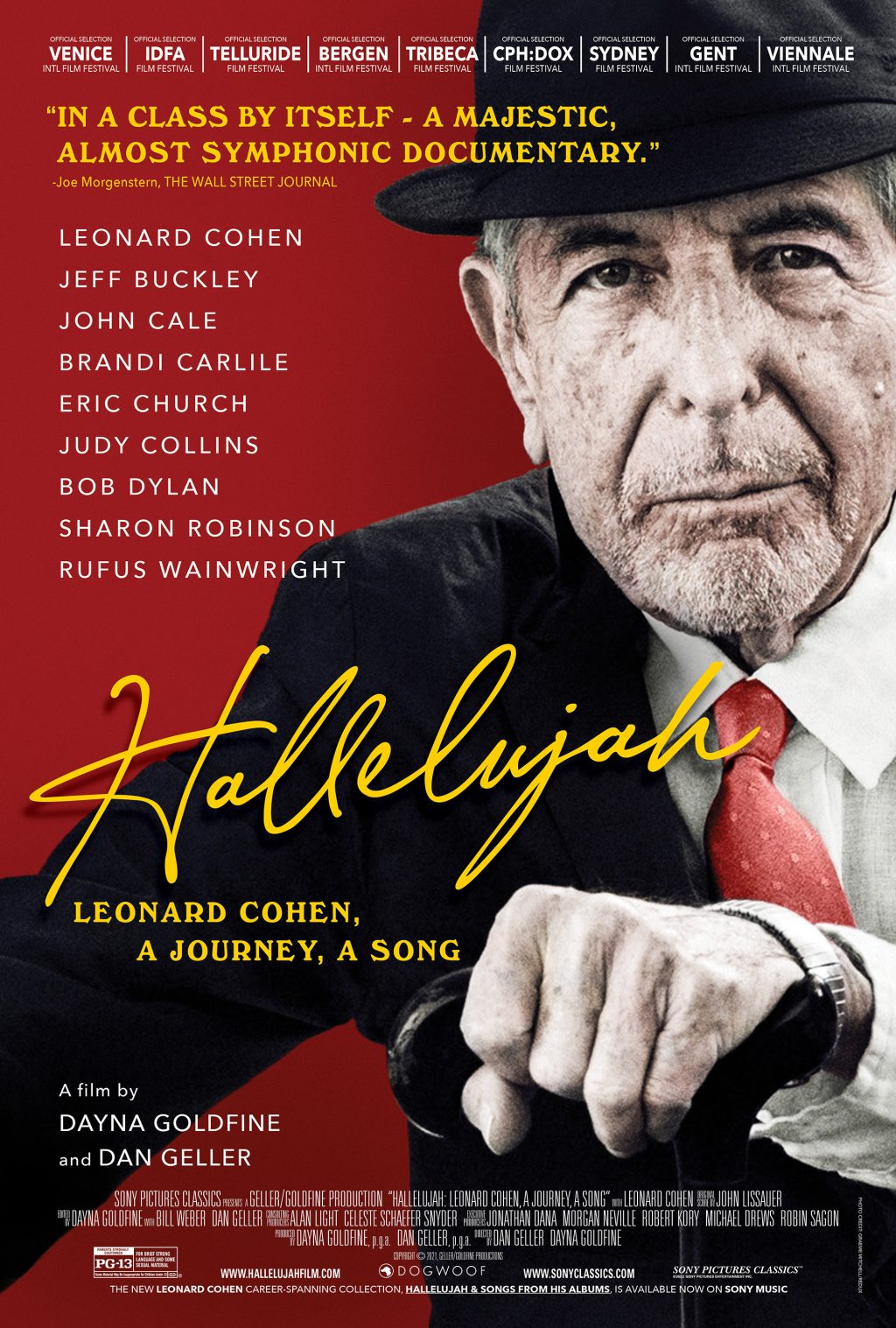

This very good documentary is more than an account of how Hallelujah came to be Leonard Cohen’s best-known song. It’s a thoughtful biography of the Canadian-Jewish poet/songwriter, told via lots of interview and concert footage. There is no overall narrator, but written subtitles tell us who, when and where.

Hallelujah is the starting-point and the prism through which the rest of the story comes, fleshed out by stops along the way to mark other personal, musical and philosophical milestones in the life of this complex, sometimes troubled artist.

In his heyday, which coincided with my impressionable student years, I wasn’t the biggest Leonard Cohen fan. I found his music gloomy, his voice monotonal and his words impenetrable. I remember a debate on Melbourne University campus in the 70s between two literary academics as to whether Cohen was a true poet like Bob Dylan, or a poseur who hid his lack of poetic ability behind a wall of pretentious obscurity. I was on the side of the Dylanite. I was wrong. I’ve since discovered numerous musical and lyrical treasures in the Cohen oeuvre, many of them showcased here. Amazing what maturity can do for your intellectual and aesthetic horizons. (Mark my words, youngsters!)

Leonard Cohen had a lot on his mind: sex, social justice, love, religion, the meaning of life, more sex and Jewishness. Hallelujah isn’t the only one of his songs to contain biblical references but as the camera shows (they had access to his handwritten notes) and the interviewees tell us, the song had a long evolution over at least a decade, as if Cohen were trying to encapsulate all his ancestral dreamings and inchoate yearnings into this one song.

Which is why there’s no definitive version of it. Some folks have counted more than a hundred potential verses. Someone with sound instincts persuaded him to record a version of it for the 1984 album Various Positions, but his record company didn’t like it and it was barely released in the USA.

The first popularizing version came, curiously, on the Shrek soundtrack, leaving out the naughty bits. Que? One collaborator gives the example ‘she tied you to her kitchen chair’. Then came versions by Jeff Buckley, John Cale and Rufus Wainwright, all of whom appear and speak.

These were all very good, IMHO, because they are performed with a minimum of vocal pyrotechnics. We see and hear later dreadful versions: over-produced, over-dramatic and emotionally incontinent productions by aspiring divas on reality TV ‘Voice’ contests, mainly. KD Lang had a hit with her studio version and I was wondering when that would pop up, but they save her for a ghastly OTT live version she performed at a tribute concert after Cohen’s death.

These low points in the popular evolution of the song are all part of the story, of course, and don’t detract from its overall interest. Fun facts pop up: the number of younger fans and industry folks, for instance, who think Jeff Buckley wrote Hallelujah.

Cohen himself remains the central figure in this story of a man described by his early collaborator and lover Judy Collins as ‘handsome, intelligent, mysterious and dangerous’. And so he was. You could add aloof, moody and morose.

One endearing and quite funny (to me) aspect of his character is that it took him, then in his sixties, six years in a strict Zen retreat in the Californian mountains to cheer up! He just decided one day he’d had enough of all that physical and spiritual rigour and he emerged, as the documentary footage shows, a calmer, apparently happier fellow who even put jokes into his schtick. No longer the tortured genius.

Six years! I was reminded of that old joke, which is a bit Zen itself, when you think about it: Why do you bang your head against the wall? Answer: because it feels so good when I stop!