I finally got around to watching this much-vaunted biopic about legendary composer/conductor Leonard Bernstein. I watched it on Netflix, whence it was consigned after a short cinema run in the United States. I normally don’t review movies I see on streamers, because there are so damn many and I can’t keep up. But it is a major movie, having racked up umpteen nominations for BAFTAs and Golden Globes and suchlike, although it didn’t score any significant wins.

It might do better in the Oscars, for which It’s garnered seven nominations already, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Bradley Cooper, who also co-wrote and directed it. I say it might do better because Hollywood likes this kind of thing, and by that I mean stories that are showy, glossy, sentimental, only superficially serious about character and where substance takes second place to style.

There’s no doubt Cooper makes a convincing Leonard Bernstein. He’s done his homework to the nth degree to capture the man’s speech, mannerisms and looks, right down to the use of a prosthetic nose. I don’t mind that a non-Jew is playing a Jewish man because I believe an actor’s job is to portray people other than themselves and that breaking cultural, ethnic or even racial boundaries to do so is fine as long as it’s respectful and as long as it works!

As for the accusation that using a prosthetic nose is akin to putting on ‘Jewface’…. I suppose that’s a bit more problematic. It wouldn’t be acceptable nowadays for a white actor to put on ‘blackface’, but it was okay for Nicole Kidman to wear a prosthetic nose to play Virginia Woolf. Hmm. I’m going to leave this thorny issue alone for now.

My quibble with Bradley Cooper’s work is that Maestro is more a showcase of his ability to do a good Leonard Bernstein impression than it is a serious biopic about this towering figure of 20th century music.

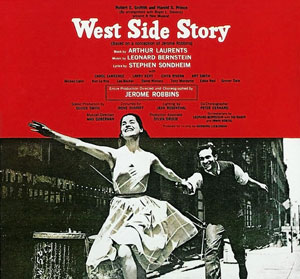

Admittedly, this would be no easy feat. Bernstein racked up so many achievements in his life that only a lengthy documentary could do them justice, and there’ve been plenty of those. He was a musical prodigy: not just a globally revered conductor of music in the classical orchestral tradition, but he also composed some of the most memorable contemporary music of the time. Think West Side Story for a start, and the score for the Elia Kazan classic On The Waterfront.

But here’s the thing: you’d think these two landmark musical achievements would feature in the storytelling, but they don’t! We do see, early on, an extended dance sequence from the musical On The Town, the one about the three sailors on leave in New York. It was first performed in 1944 and went on to have umpteen productions on Broadway and elsewhere, but in its most famous production, the 1949 movie starring Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra, only four of Bernstein’s songs were used in the soundtrack. One of them was the enduring classic New York New York (‘it’s a wunnerful town’), but why showcase that one and leave out his contemporary masterpiece West Side Story, for which he wrote the whole score?

And it’s not that Maestro ignores his classical achievements. The movie starts with him getting his big break as a conductor in 1944 when he was called on at short notice and without rehearsal to fill in that evening to conduct the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. He pulls this off magnificently and is suddenly the toast of le tout New York.

We see plenty of spirited conducting and teaching thereafter, and Cooper has even gone to the trouble at the end of the story of moving production to Ely Cathedral in the UK to recreate Bernstein’s landmark 1973 performance conducting the London Philharmonic in Mahler’s Second Symphony.

Defenders of the movie will remind us that its central focus is Bernstein’s relationship with his wife, the Chilean-born actress Felicia Montealagre, played here by Carey Mulligan, who was a successful creative artist in her own right. It’s an interesting story.

They met in 1946, at a party given by his piano teacher, Claudio Arrau. Bernstein said they fell in love that very night, and they got engaged later that same year. However, Bernstein was famously bisexual, and most of his relationships both before and after he met Felicia were with men. She knew about it, of course, and their marriage endured and produced three children, but it did cause huge emotional turbulence in both their lives.

She even left him early on in their engagement for three years, to take up with actor Richard Hart, whose death from a heart attack in 1951 ended their relationship and she went back to marry Bernstein. This episode is not addressed in Maestro, which is curious given what the movie otherwise leaves out to concentrate on the marital relationship.

It skips a whole crucial decade and a half in the couple’s life, leaping from the mid-fifties to 1971 as if his tenure as music director of the New York Philharmonic, the creation of West Side Story and their turbulent political life during the nineteen-sixties were of less significance than the personal story, of which the main elements have already been established: their profound mutual affection, the understanding that he could live his double life as long as he was discreet (which he wasn’t), and his eventual return to the family fold to look after her when she was dying of breast cancer.

That’s my problem with Maestro in the end: there’s too much repetition of the deep-and-meaningful heart-to-heart stuff when the time could more profitably have been spent telling this emotional and personal aspect of the story through the lens of their professional and creative lives.