Cards on the table. I’m a bit of a Napoleon groupie. I think he’s one of the most fascinating figures in history.

I saw the movie the first day it came out at my local cinema. I started writing this review, but got bogged down trying to work out why I was disappointed in it, despite its excellent production values and at times wonderfully adept recreations of moments in the great man’s history.

Then I came across a review by a bloke called Mark Lopez. This is how he started:

I have admired Napoleon since I was eight. In my library I have many hundreds of books on him, on his battles, and on this period, including memoirs by his soldiers, his commanders, his government officials, his domestic staff, by illustrious women of the court, and by his opponents. I have gone to France several times, to walk the places he walked and to visit the palaces where he lived and worked. I even went to Belgium to traverse the battlefield of Waterloo.

A kindred spirit! I can’t claim to have hundreds of books about Napoleon, but I too have made the pilgrimage to Waterloo. I haven’t been to Corsica, where he was born, or to Elba, site of his first exile, or to St Helena, his place of final exile and death, but they’re on the bucket list. I have been to Les Invalides in Paris where his body now lies in a grand and dignified setting. The French still deeply honour their most famous son. Plus I know the words to lots of old songs about Napoleon.

Lopez goes on to say he’s also an admirer of director Ridley Scott, whose 1977 debut The Duellists he says is one of the best films ever about the Napoleonic era. He says when he heard that Scott would be making a biopic about Napoleon, this time with an enormous budget ($200 million) and with computer generated imagery at his disposal, it was like ‘a dream come true’ and he counted the days till its release.

However, he continues: Unfortunately, all this cinematic account of Napoleon’s life has in common with history is some names and dates, the rest is made up. More than being an account of Napoleon’s eventful life it is a cinematic hit job on his memory and legacy. Napoleon is used by Ridley Scott to attack his concept of a tyrant, when Napoleon, a man of the Enlightenment, was not a tyrant, not remotely.

This is an ahistorical film from start to finish, supposedly covering Napoleon’s life from 1793, when he got his start as a young artillery officer, to his death in exile in 1821. Yes, there is room [for] poetic licence, but there is a limit. ….. You can play around with facts regarding Roman emperors and gladiators and get away with it, especially if you make a great movie, as was the case with …. Gladiator. But Napoleon is a figure from modern history and much is known about him.

Napoleon did not fire artillery at the pyramids at Giza, as depicted in the film. In fact…. he brought over a hundred scientists with him on his Egyptian campaign. This led to the discovery of the Rosetta stone, which ….. facilitated the translation of hieroglyphics and changed Egyptology for the better forever. ….. There were no trenches at the battles of Austerlitz or Waterloo, and Napoleon never led a cavalry charge. The falsehoods are so many they are too numerous to mention.

Wow. I have to bow to superior knowledge here. Elsewhere on the internet I learned that Napoleon spent the three months he was in control of Cairo introducing street lighting and cleaning, reforming the tax system to place less of a burden on the Egyptian peasantry, building modern plague hospitals, and changing the city’s administrative structure so it was no longer feudal. He also established a scientific institute to study mathematics, physics, political economy, and the arts.

This is one of the film’s big failings. It doesn’t show us anything of the man’s genius as a progressive and moderniser, a man of science and a political reformer. In the five years after he became chief consul of France in 1799, he worked tirelessly, with astonishing energy and determination, to turn France from a feudal monarchy into a modern republic based on the principles of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity. He even devised an entire legal regime – the Code Napoleon – based on the existing mishmash of Roman and local customary law. It was so good it’s still in use, with some modifications, throughout much of Europe. The Japanese took it on in its entirety when they decided to go modern in the late 19th century.

These achievements earned Napoleon the admiration and support of progressive thinkers all over Europe: people like Beethoven, who devoted his third symphony – Eroica – to a man he saw at the time as a hero and a great hope for the future. He later retracted that dedication after Napoleon made himself Emperor and showed himself to be an idol with feet of clay. Of that more later.

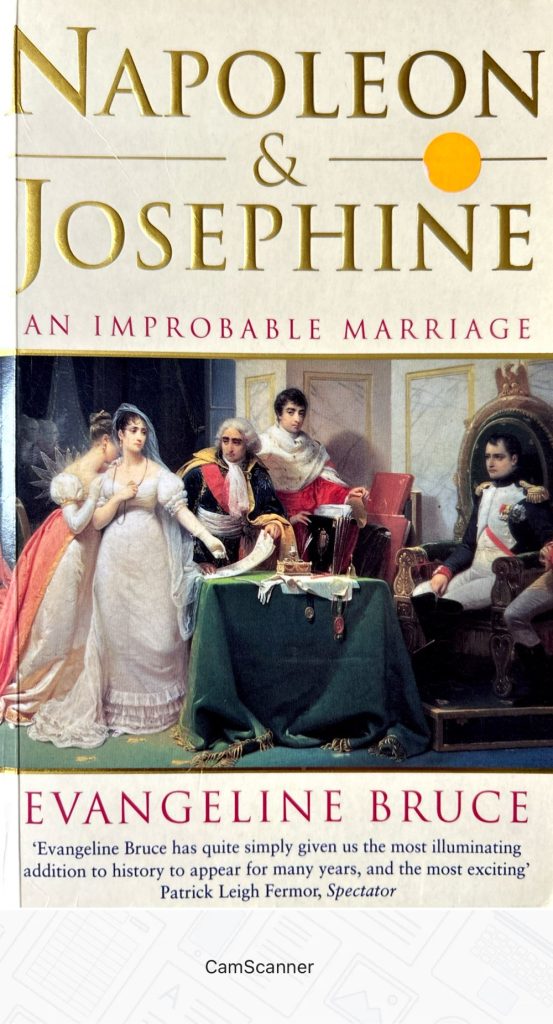

Scott admits to prioritising Napoleon’s relationship with Josephine over historical events, but here too he falls short. He does capture something of the sexual passion that bound the two, but leaves out the interesting bits. I know something about this because I’ve read this book (below) twice.

Josephine was six years older than Napoleon. Okay, it’s hard for a filmmaker to convey the transition from slim unlined youth to stout middle age, but Scott doesn’t seem to have made any effort with Joaquin Phoenix to reflect that change. So Josephine looks like a sexy young thing who caught the eye of a mature man. In fact she was a widowed mother of two children who’d endured considerable trauma during the Terror when she was imprisoned along with her estranged husband and they both faced the guillotine. She courageously spoke out to try and save him when his name came up, and only narrowly avoided the same fate herself. She was released from prison just five days after his execution, after the sudden downfall of the cruel fanatic Robespierre and the end of the Terror.

All accounts of Josephine stress her sophistication, her elegance and her intelligence. Vanessa Kirby does a passable job, but doesn’t capture these qualities.

Napoleon was a rising young military officer when he met Josephine. She took him on because her then lover, the powerful Paul Barras, had tired of her and thought she’d be good for the career of his protégé, Napoleon. She was. They were very well-matched emotionally and intellectually. Scott inexplicably portrays Napoleon as a brutish, selfish lover, but while he captures something of Napoleon’s sexual obsession with Josephine he misses the deep tenderness and intimacy that developed between them, and which survived their mutual sexual infidelities. As they grew older and he became more powerful, Josephine became more devoted and faithful while Napoleon became less so because of his desperation to have an heir. The emotional power balance had turned around. But Napoleon continued to love Josephine. He gave her property and jewellery after their divorce, settled her bills, and continued to seek solace and counsel in her company. He also continued to advance the interests of her children, Hortense and Eugene, of whom he was very fond. In fact it was through them (and his brother Joseph, who married Hortense) that he founded a kind of European step-dynasty, whose descendants throng the royal families and elites of Europe to this day.

None of this is captured in the movie.

There are some wonderful moments that are, such as the reportedly true story of when the young Eugene De Beauharnais comes before the newly-risen Napoleon to petition humbly for the return of his father’s sword. Napoleon hadn’t met Josephine at this time and didn’t know the boy, but he had the authority to go through the confiscated property of executed aristocrats, pick out a sword and oblige the boy’s request.

The period evocation is also excellent – the candlelit interiors, the dirty chaos of the post-revolutionary streets, the radical fashions in clothing. Scott has Napoleon meeting Josephine at one of the Survivor’s Balls. These were manic affairs at which those who had escaped the guillotine celebrated riotously, enacting ghastly charades of beheading and bloodshed, the women clad in diaphanous see-through garments with red chokers round their necks. The costuming is spot-on.

However. Another big failing is that Scott doesn’t show us what it was about Napoleon that so inspired the love and loyalty of his countrymen and women.

Mark Lopez tells it like this: ….in 1815, Napoleon returned from exile with his thousand guardsmen and walked from the south of France towards Paris. He could have been rejected in every town, but French men and women flocked to support him. When the fifth infantry regiment was sent to stop him, he walked up to them alone, facing their phalanx of aimed muskets. When the commander of the fifth regiment ordered his troops to fire on their former emperor, not one soldier discharged his musket, each making the individual decision not to do so, having no idea that all their comrades were thinking the same. This is one of the most extraordinary moments in history, and it is deliberately played down in the film to deprive Napoleon of this indisputable demonstration of his courage and charisma.

He continues: In the closing credits, the filmmakers [depict] Napoleon as responsible for the collective deaths of the wars of the period. But almost all of those wars were imposed on France by its enemies. Instead of France being overrun and having another political system imposed on it by its foes, under Napoleon’s leadership, he defeated the enemies, conquered them, and imposed the best of the French Revolution on them. ….To blame Napoleon for the collective military deaths of an era of conflict that started long before he had a say in what happened is unfair and just plain wrong.

I can’t help but continue to quote Lopez because he’s so spot-on: Napoleon does deserve criticism for a number of the war dead. His disastrous strategic decisions in the invasion of Russia in 1812 that lost ninety percent of his army spelt the beginning of the end. He should have consolidated what was left of his empire, but instead he raised new armies to attempt to win back his losses only to be strategically defeated in costly campaigns in 1813 and 1814.

Napoleon was a flawed character – a political and military genius who tended to confuse his personal ambition with the overall interests of France. His was a glorious rise to power and achievement followed by a downfall due to his inability to know his own limitations. Scott’s Napoleon flattens this grand trajectory. But if you don’t give us the highs, you miss the drama and the tragedy of the lows. Napoleon should have been a more moving and thrilling movie than it was.

Fun fact about Napoleon: it was he who thought up the system of numbering street properties with evens up one side and odds down the other.