Nitram is an examination of the life of the Port Arthur gunman in the time leading up to the mass murder he perpetrated there in 1996.

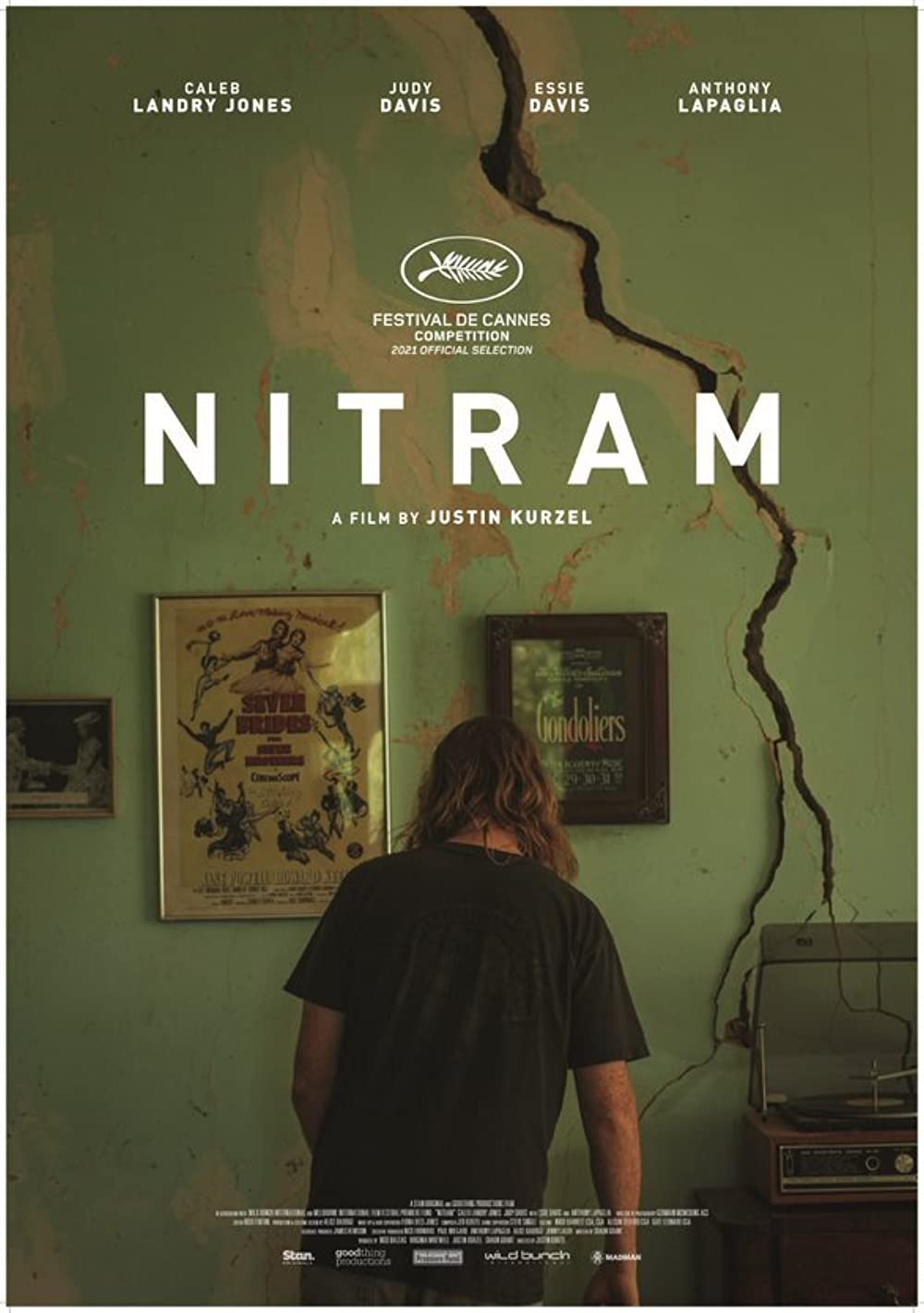

Nitram is his real name spelt backwards. As depicted in the film, it’s a childhood nickname bestowed by bullying schoolmates mocking Nitram for his backwardness. It’s a nickname he hates and isn’t able to shake. The filmmakers – director Justin Kurzel and writer Shaun Grant – believe this was true in real life. I was unable to find confirmation of this, but it could well be so.

Real or not, naming the central character this way is a concession to the sensibilities of survivors and the wider community, the idea being to deprive the murderer of further notoriety by not saying his name. Jacinda Ardern expressed the same sentiment and adopted the same convention after the Christchurch mosque shootings. I will do likewise and refer to the real person as the gunman and to the film character as Nitram.

The subject matter of the film is so controversial that there has been serious opposition to its being screened, or even made, for that matter, especially here in southern Tasmania where I live, and where persistent trauma was inflicted on this small community where just about everyone either knew or knew of the gunman or had some connection to his family or to one or more of his victims, myself included.

I had no hesitation in wanting to see Nitram. I’d read and heard enough commentary to know it was neither sensationalist nor graphically violent. It does not depict the actual killings but is no less powerful and shocking for that.

I wanted to see it for the same reason I’ve willingly visited the killing fields of Cambodia and Nazi death camps: to face up to human evil-doing and try to understand it. As well, at some level I believe it’s a way of remembering and honoring the victims of evil. I understand why some people don’t share my views.

The film opens with footage of the real person as a boy in the Royal Hobart Hospital burns unit. A TV reporter has been sent to get him to tell the story of how he got there, and whether he’s learned his lesson about playing with fire. His answer is the perfect introduction to the strange dark character who was, it seems, born that way: a nutcase, a misfit.

It’s also the only scene taken from real life. In another concession to Tasmanian sensibilities, Kurzel and Grant shot the film in Victoria, at locations that are good proxies for the familiar notorious landmarks but not so similar that they might ‘trigger’ vulnerable viewers. Interestingly, it uses the real names of his parents and that of the Tattslotto heiress whose relationship with Nitram was to prove so crucial to the dreadful outcome of the story.

Otherwise it remains essentially faithful to the facts if not literally so. One adjustment made for narrative and dramatic purposes was to compress the time line. The story appears to take place over a period that looks like about two years. We see Nitram’s fateful first meeting with Helen Harvey during this time. In reality it had happened nearly a decade before, but like other elisions and absences, such as the extent of his aimless international flying, it doesn’t affect the essential truth.

The film does take a position on certain aspects of the real story that have remained unresolved or controversial, such as the manner of Helen Harvey’s death and that of Nitram’s father.

It also takes an unambiguous position on guns. In what I think is the film’s most powerful and harrowing scene, Nitram goes into the scuzzy suburban gun shop and is shown around and invited to handle the merchandise by a salesman who doesn’t bother to ask why this creepy-looking weirdo with a bag full of cash wants to acquire such a potentially devastating armoury of weapons and ammo. Not even when the weirdo admits he doesn’t hold a license and has no intention of registering the guns. There’s nothing melodramatic about the scene; it could be taken from documentary footage if there’d been CC-TV in the shop. It was the one time I closed my eyes, shook my head and almost screamed inwardly no, please God don’t let this happen!

Nitram is a brave and original film. Brave because it looks squarely at an act of shocking savagery and tries to make sense of what makes a particular human being act this way. Original because there is nothing like it already in popular culture or accepted wisdom that can help us with this case. The gunman doesn’t fit into the any of the expected categories: he wasn’t acting out the effects of an abusive childhood as is so often the case with violent offenders, and he wasn’t a cold and calculating psychopath like the protagonist of We Need To Talk About Kevin, a fictionalised portrayal of the young perpetrator of a school killing spree in the United States.

Nitram humanises this problematic figure without excusing his actions. In this I think it compares to the work of Hannah Arendt, the German-Jewish writer who attended the trial of Adolph Eichmann, one of the chief organisers of the Holocaust, noting how ordinary he was, how quite un-monstrous notwithstanding the monstrous evil he unleashed on the world.

The gun shop scene in Nitram reminded me of this insight of Arendt’s into what she came to call the banality of evil.

Young US actor Caleb Landry-Jones embodies Nitram, a resentful and unlovable young man slow on the uptake, stubbornly resistant to good advice, a natural target for bullies. Who dreams of being a surfer but is always on the outer with the cool crowd. Who knows people think he’s a retard. Who wants people to like him but can’t stop himself doing things he knows will annoy them. A pathetic, vulnerable character, childlike in his inability to govern his own emotions. It’s a brave and brilliant performance and Landry-Jones deserves the Best Actor award he won at Cannes this year, along with the standing ovation.

Judy Davis plays Carleen Bryant, the thin, chain-smoking mother harried to near-exhaustion by her intractably troubled son. Anthony La Paglia plays Maurice Bryant, the well-meaning father too preoccupied with his own failures to be any help to anyone.

Justin Kurzel’s wife, Tasmanian actress Essie Davis, plays Helen Harvey, the ageing rich lady living alone in her crumbling mansion like some kind of mad princess, endlessly playing her Gilbert and Sullivan records and surrounded by the dogs and cats who are her only companions until the day another crazy loner enters her life…

All performances are flawless.

Nitram is a highly moral and profoundly disquieting film that raises new questions about how society interacts or should interact with the disturbed, alienated loner. I think it’s a masterpiece.