How can I save my little boy from Oppenheimer’s deadly toy?

I’ve had this line from Sting’s song Russians going through my mind ever since Christopher Nolan’s blockbuster biopic about the architect of the atom bomb entered pop culture.

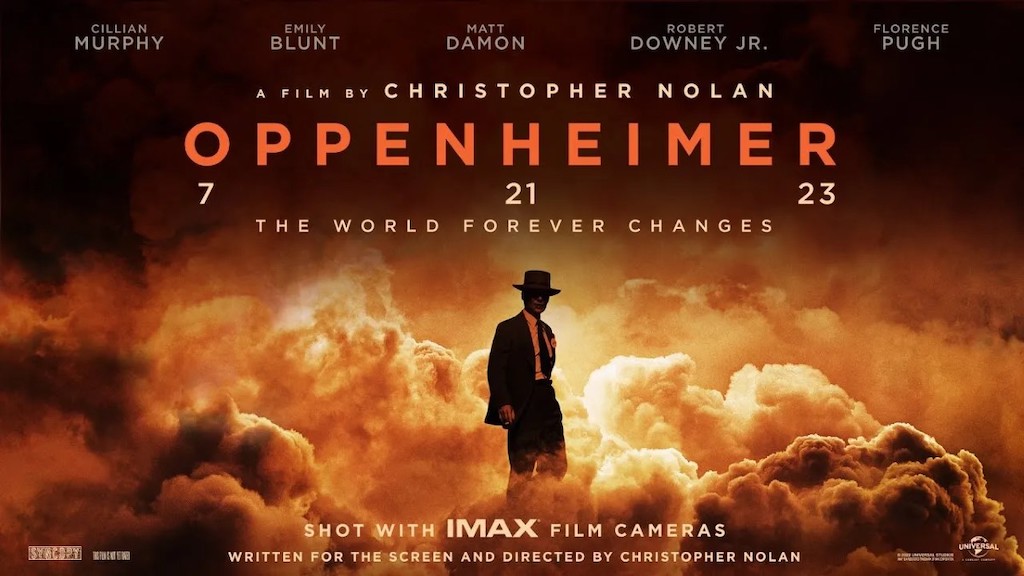

There’s no doubting the gravity of the subject matter of Oppenheimer, but it must be Nolan’s authorship that accounts for the hype and the popularity. As the maker of sci-fi-tinged masterpieces such as Inception, Interstellar and Memento, as well as more conventional fantasy stuff like The Dark Knight, he’s the uber-cool director du jour.

Either that or the Barbenheimer phenomenon – the fact that Barbie and Oppenheimer were released on the same day. It’s spawned a vast amount of social media commentary about the contrasting subject matter of the two movies, as if this had some intrinsic cultural significance. But they were made by different studios – Universal and Warner – which engaged in the usual Hollywood power-play over release dates, but the coincidental release was no big deal.

At least not for a baby-boomer like me who’s more interested in the movie’s content than in pop cultural meta-phenomena, although I do quietly enjoy the fact that a story about a real scientist who did something significant – for good or ill – has become such a success.

Stories about scientists usually tend to appeal to a niche audience – think The Theory of Everything, about Stephen Hawking, or A Brilliant Mind, about the mathematician John Nash, or The Current War, about Thomas Edison, or The Imitation Game, about Alan Turing. Mind you, that latter did earn quite a lot of money and an Academy Award, but only for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Anyway, I’m in that niche group. I love true stories, especially biopics, and especially stories about scientists or STEM heroes.

The plot traces the life of Robert Oppenheimer from his early days as a promising young physics student studying and teaching in both Europe and America through to his instalment as head of the Manhattan Project … and beyond, to a time and place where his political affiliations cause him to fall foul of McCarthyism.

It’s this ‘beyond’ which I think is the film’s only failing. You’ve heard that it’s long – 3 hours long – and I think it’s pointlessly long. This is because of the stringing-out of the post-Hiroshima feud between Oppenheimer and Lewis Strauss, one of America’s most important Cold War advisers on atomic matters.

Initially an admirer, Strauss had recruited Oppenheimer as Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton after the war, despite the deep-seated differences between the two men on Cold War politics. Strauss was angry and humiliated when a Congressional Committee in 1949 sided with Oppenheimer rather than Strauss over the export of radioactive isotopes.

Strauss then tried to have Oppenheimer’s security clearance revoked, playing on the then prevalent fears about Communists in public life. Oppenheimer had been, like so many intellectuals in the pre-war period, sympathetic to socialism, as were several of his students and his brother Frank, who was more of a genuine communist than Robert. Their Jewishness didn’t help, and their careers all suffered to a greater or lesser degree under McCarthyism.

It’s a long and complex story, too long to even check out how Nolan’s depiction squares with the facts. (Try googling and see just how long a story it is.) I’m sure he got the essence of it right, but the sheer volume of detail, and the pace at which Nolan has tried to cram it all in, drags the story down in the second half.

The film also suggests that Strauss’s hostility to Oppenheimer was further entrenched because he thought Oppenheimer had said something nasty about him to Einstein, then a revered figure at Princeton. As a device for illuminating the personality conflict between Oppenheimer and Strauss, this works well dramatically, and also provides a nice rounding-off moment at the end when it is revealed what Einstein really said to Oppenheimer.

Cillian Murphy plays Oppenheimer, and it’s truly masterful how he takes the character from idealistic young brainiac to mature scientist and administrator weighed down by the moral gravity of what he’s done.

Robert Downey Jr is almost unrecognisable as Lewis Strauss in another bravura performance.

Kenneth Branagh plays Neils Bohr, one of the many pioneering scientists of the nuclear age who appear in the story. There’s also Enrico Fermi, Richard Feynman and Klaus Fuchs, the scientist who handed all the Americans’ atomic secrets to the Russians because he believed no one nation should have a monopoly on such dangerous and powerful knowledge. He doesn’t have much of a speaking part but the consequences of his actions are given the importance they deserve.

The wonderful Tom Conti plays Einstein. All the characterisations are so good, not just of the scientists but note also Gary Oldman as Harry Truman. In one crucial scene Truman calls Oppenheimer in to thank him for his contribution to….everything: the war effort, science, American military power. Oppenheimer confesses to the President his agonies of conscience about having Japanese blood on his hands. Truman’s response encapsulates the clash between moral and political imperatives that’s at the heart of the story.

To his credit, Nolan sticks to straight storytelling and doesn’t muck the storyline about too much with arty cinematic pyrotechnics, although the recreation of the atom bomb explosions is brilliant. I read or heard somewhere that there was no CGI in the creation of these sequences. He’s managed to achieve his powerful and awesome effects with real explosion footage.

As I’ve been working on this review, the words of Sting’s song keep coming back to me:

There is no monopoly on common sense

On either side of the political fence

We share the same biology, regardless of ideology

Believe me when I say to you

I hope the Russians love their children too.

I’ve decided it’s his best song ever. Look up the full lyrics and you’ll see what I mean. He wrote it in 1985 and says it’s more relevant than ever due to the war in Ukraine. He posted a video on Instagram of himself singing it. In the caption he wrote, “I’ve only rarely sung this song in the many years since it was written, because I never thought it would be relevant again.”

Sigh.