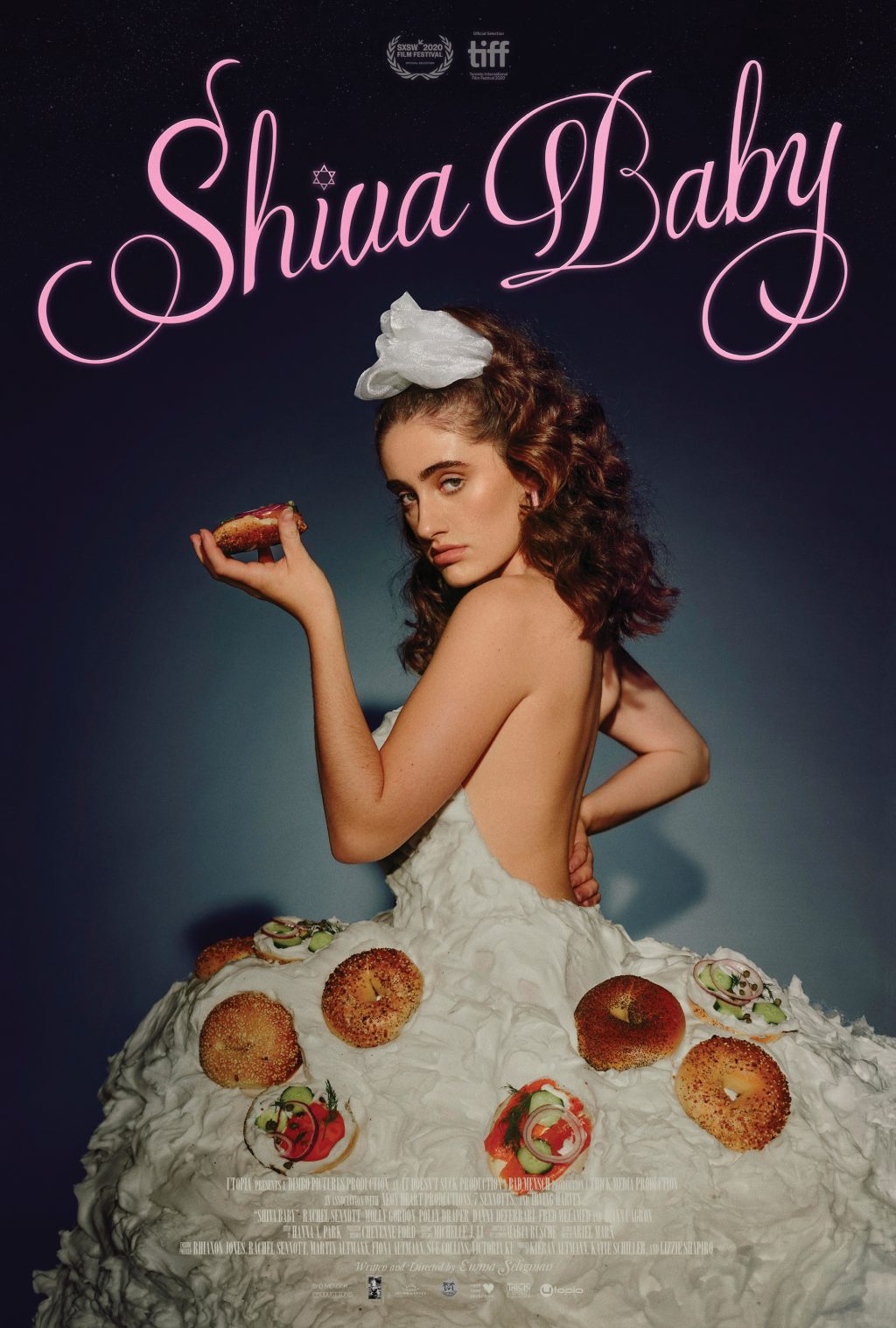

Shiva Baby is about a couple of hours in the life of young New York Jewish woman Danielle.

When we first meet her she has just had sex with a man – Max – in his apartment. Her mobile rings. It’s her mother, reminding her that she’s promised to accompany her parents to a shiva – a gathering, akin to an Irish wake, held at the home of the bereaved after the actual funeral.

Danielle gathers up her things and prepares to leave, but not before extracting some cash from Max. It’s clear this is part of a regular arrangement in which he pays her for sex, although he doesn’t seem much older than she is.

Danielle arrives at the shiva home just as her parents do. Her mother is too busy kvetching about her father – he doesn’t listen, he forgets what I tell him, he’s got Alzheimer’s – to quiz Danielle about why she skipped the funeral or what she’s been up to. Like the typical over-involved Jewish Momma she has an agenda beyond shiva observance: it’s to hustle her daughter’s prospects, and she issues sundry instructions to Danielle on how to behave and what not to say in front of this multi-generational and high-achieving tribe which might just contain potential employers or marriage suitors. It’s all Danielle can do to get a word in begging her mother to remind her who’s died. They go in.

What follows is a kind of screwball comedy/psychodrama for the millennial age.

Danielle is bisexual and has recently broken up with Maya, who’ll also be at the shiva. Her parents know about Maya and are sort of cool about it because Maya is a success story who’s got into Law School. There’s unfinished emotional business between the two girls, but mother’s orders are that there’s to be no ‘carrying on’.

Nobody knows about Max. Danielle’s story is that her money comes from babysitting and that she’s got job interviews lined up. Maya is suspicious. Then Max turns up at the shiva. Danielle is deeply discombobulated. Neither of them knew about the other’s connection to this crowd. Her inner turmoil ratchets up when Max’s shiksa wife Kim arrives with their new baby. Danielle did not know about them either.

Danielle may have her generation’s insouciant and entitled attitude to sex and sexual orientation but she’s just as emotionally insecure as the next twenty-something in matters of the heart. Then there’s the competitiveness issue: Kim is not only a gorgeous blonde but also an enterprising businesswoman who appears to be good at both career and motherhood. Meanwhile Danielle’s cover story about the babysitting and the job interviews becomes increasingly difficult to sustain under cross-examination by people who’ve known her since she was a baby. These nosy folks also want to know how come Danielle and Max seem to know each other. So does Maya. Her parents are no help: her doting dad keeps telling cringe-making stories about Danielle in childhood, and her mother actually hustles Kim to give Danielle a job – in her presence! How embarrassment, as Effie would say.

Danielle has all the attitude you would expect from a millennial JAP (Jewish American Princess) but behind the casual profanity and verbal bravado she’s deeply perplexed about the Max situation, and she doesn’t want her parents – or anyone, really – to think she’s a slacker.

Shiva Baby reminded me a bit of Seinfeld in that it all takes place in the one setting with the same rapid-fire banter, but without the laughtrack. With its serious undertones and its angsty central character it’s also reminiscent of Woody Allen, who used to be the master of this kind of thing until his fall from grace. First-time director Emma Seligman could well become his replacement for the gender-fluid post #MeToo age.

Its short running time of 77 minutes redeems Shiva Baby from the oppressive emotional intensity that might otherwise have arisen from the claustrophobic setting and the unrelenting use of facial close-ups. I loved it.

Fun facts: the actress who plays Danielle – Rachel Sennot – isn’t Jewish, but Dianna Agron who plays the only non-Jewish character in the story, is!