This film tells the story of Rudolf Nureyev’s defection to the West in 1961 and the events leading up to it.

It’s not as simple a story as you might think. Numerous writers, athletes and artists defected from the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and it was an easy assumption that they were fleeing tyranny and looking for freedom. There is of course much truth in this view, but it’s not the full picture. Look at Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the great Russian writer and chronicler of the worst of Soviet repression. He managed to get out after years of anguished struggle, but decided in the end that life in his blighted homeland was preferable to the materialism, philistinism and soullessness of America, and he went back!

I don’t know if things have changed now that so many years have passed since the fall of the Soviet Union, but stereotypically Russians have always had an intense, some might say spiritual bond to their homeland and its earnest, soul-searching culture, a bond which endures beyond separation and the horrors of whatever regime is currently in power.

Ralph Fiennes understands this. Turns out he’s quite the Russophile. He co-produced The White Crow as well as directing and starring in it – speaking fluent Russian – as Alexander Pushkin, not the famous writer but the revered dance teacher into whose class the young Rudolf pushes his way in the unshakeable belief that he deserves the best.

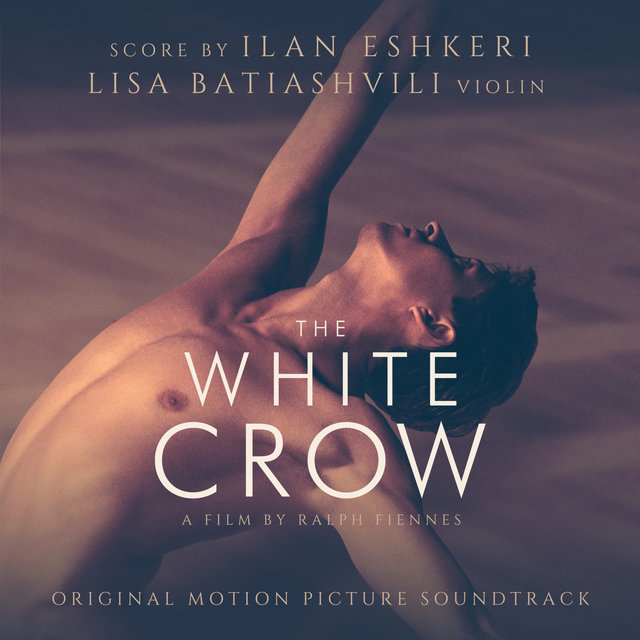

That belief had its roots in his childhood as the adored only son of a Tatar Muslim family. His father was a Red Army political commissar; his mother and his three older sisters all believed in his exceptionalism. Nothing about him was ever ordinary. Even his birth was exotic: he was born on a trans-Siberian train, a fact he relished and associated with his own drive and ambition. The film’s title itself, The White Crow, is a reference to Rudolf’s childhood nickname; it’s a Russian phrase meaning something or someone exceptional.

The story is told in three intertwining timelines: his childhood, where he disdained the games of his playmates to immerse himself in Bashkiri dance culture, his early adulthood at ballet school in St Petersburg, the fateful visit of the Kirov Ballet to Paris in 1961.

It starts at the end, really, with his teacher Pushkin (Fiennes) being grilled by the KGB on what he knew about Nureyev’s defection, and swoops back and forth among the three timelines. Fiennes uses differing colour schemes – grey monochrome for the bleak landscape of wartime Soviet Union, washed-out pallor for Cold War Leningrad, a more naturalistic palette for 1960s Paris – to delineate the times and places.

The artiness and the style are not overdone and don’t detract from the terrific central performance of young Russian dancer Oleg Ivenko, making his acting debut as Nureyev.

Not only does he look like him, he’s also managed to capture the essence of Nureyev’s personality: his arrogance, his rebelliousness, his artistic intensity.

This intensity wasn’t restricted to ballet. Nureyev had an enormous hunger for culture in all its forms – architecture, sculpture, painting, music – and he was like a kid in a lolly shop from the moment he arrived in Paris. He would be up before daylight and awake long into the night in his passion to take it all in, to the great chagrin of his KGB minders, of course.

The events leading up to the defection make a surprisingly suspenseful story, and Fiennes takes his time to tell it in all its gripping detail. Of course we know the eventual outcome, but to what extent it was planned and what exactly Nureyev’s motives were are still debated to this day. The White Crow sheds light in an admirable and enjoyable way.

I loved this movie!